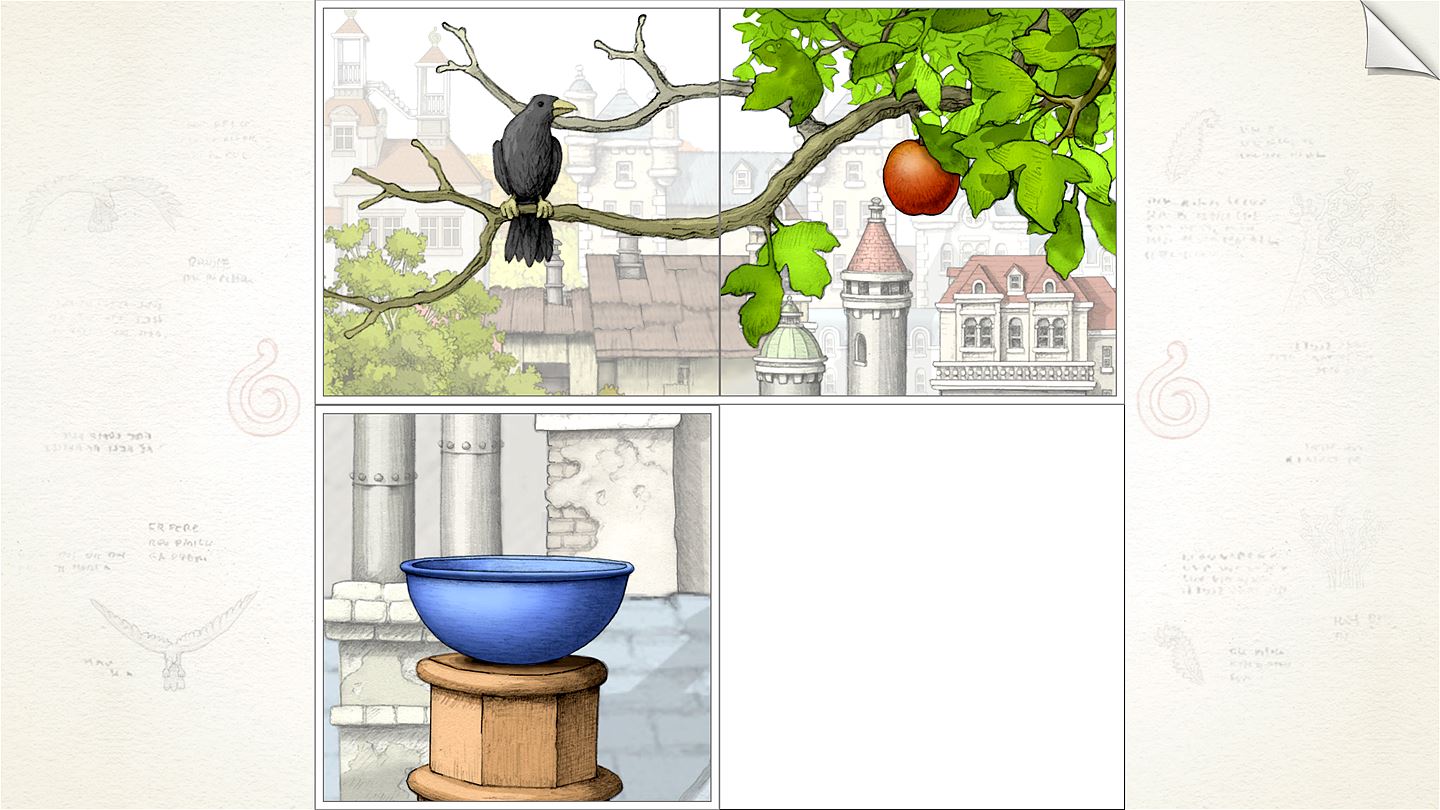

In his teenage phase, the panels are already in motion, and must be carefully moved so as to account for the objects within them. The panels with the boy alone involve interactions with simple, pretty pictures-of a black raven atop a branch, a red apple hanging from a tree, and a blue bowl sitting on a pedestal-that spring to life when properly aligned. Accordingly, the puzzles grow more elaborate throughout his adolescent years and adulthood before slowly becoming simpler when he’s in his senescence. This concept is made concrete by the haunting passage of time within the game, for it soon becomes clear that many of the panels, despite occasionally interlocking and sharing a fixed space, often depict moments from different points in the boy’s life. By keeping things so simple, the game is able to keep our focus entirely on the joy of discovery, delivering a striking visual metaphor for the way in which we form memories and, from those, tell stories. Panels can sometimes be zoomed in and out of, or panned from side to side, and they can be overlapped or connected adjacently to make new images and connections. Gorogoa’s controls never get any more complicated than that. When you do so, Gorogoa’s simple mechanic springs to life, for there are now two panels: one is the familiar image of those rooftops, and the other is the window itself, now looking out at an empty whiteness of infinite possibility.

The game gives you no directions, only an invitation to experiment, to perhaps move that panel from one square to another. As a boy gazes at the creature in awe, the camera pans back again, the panel now set on a grid of four adjacent squares. With the click of a minus sign, the camera pulls back, re-centering the image of the town, which is now glimpsed through a window frame. A colorful, dragon-like creature rolls down a street, partially obscured by the roofs of buildings in a quaint town. The puzzles in Gorogoa begin with just a single panel, a single story, a single perspective.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)